http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/

http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/

Christianity entered into the world not to be understood but to be existed in

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.  Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.  Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.  Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus  Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus  Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus. Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the first two chapters of Exodus.

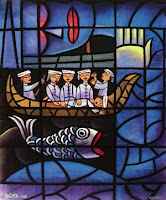

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the literary aspects of the book of Jonah.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the literary aspects of the book of Jonah. Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the literary aspects of the book of Jonah.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the literary aspects of the book of Jonah. For those (one or two) interested, there is a new English translation of the Septuagint (NETS) available for free online in pdf format.

For those (one or two) interested, there is a new English translation of the Septuagint (NETS) available for free online in pdf format. Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the literary aspects of the book of Jonah.

Old Testament thoughts is a weekly post where we'll be looking at some interesting aspects of some Scripture from the Hebrew Bible (what Christians call the Old Testament). Right now, we are looking at the literary aspects of the book of Jonah.

Still in Chapter 1, there are a few other nice literary features in the text to consider.

Still in Chapter 1, there are a few other nice literary features in the text to consider. I have been posting about the literary aspects of Jonah over at the Encounter blog and thought they would be good to reproduce here. Comments, critiques, and questions are helpful.

I have been posting about the literary aspects of Jonah over at the Encounter blog and thought they would be good to reproduce here. Comments, critiques, and questions are helpful. I wanted to advertise for the new Reader's Hebrew Bible that will be coming out in March that Pete told us about a few days ago. I have to admit I am excited. I use my Reader's Greek New Testament all the time, it was one of the best things I've ever bought for my study. The Hebrew Bible will contain in the footnotes all vocabulary occurring 100 times or less in the HB. It really does allow me to spend more time in the text and less time in the lexicon while at the same time not really losing any valuable study since I would be doing the same thing in a lexicon as I would by looking at the bottom of the page. The only downside is the lack of a critical apparatus but that allows for a much slimmer and light-weight Bible. I wonder if it would be okay to duct tape the Reader's GNT to the new Reader's HB?

I wanted to advertise for the new Reader's Hebrew Bible that will be coming out in March that Pete told us about a few days ago. I have to admit I am excited. I use my Reader's Greek New Testament all the time, it was one of the best things I've ever bought for my study. The Hebrew Bible will contain in the footnotes all vocabulary occurring 100 times or less in the HB. It really does allow me to spend more time in the text and less time in the lexicon while at the same time not really losing any valuable study since I would be doing the same thing in a lexicon as I would by looking at the bottom of the page. The only downside is the lack of a critical apparatus but that allows for a much slimmer and light-weight Bible. I wonder if it would be okay to duct tape the Reader's GNT to the new Reader's HB?