Although there are dozens of other great literary features in the book of Jonah (like chapter 4's affinity with the book of Exodus) I will end this series with a discussion of how the Ninevites are portrayed in the book. The book makes it sound as though the Ninevites are no better than cattle.

Now, oftentimes, the Old Testament will call people animals. For instance, Amos rails against some foreign wives and says, "Hear this word, you cows of Bashan who are on the mountain of Samaria, who oppress the poor, who crush the needy!" But there in Jonah the comparison between the foreigners and cattle is a little more subtle.

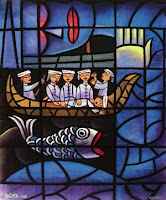

This idea is seen in Jonah 3:7-8 and 4:11. In 3:7-8 the author lumps man and beast together in the proclamation of the king of Nineveh who says:

"Do not let man, beast, herd, or flock taste anything. Do no let them eat or drink water. But both man and beast must be covered with sackcloth and let them call on God earnestly that each may turn from his wicked way and the violence which is in their hands." So both man and animal (what a strange idea) must be covered with sackcloth (a traditional Hebrew rite for mourning) and let them (another strange idea) call on God.

Then in 4:11 he also lumps them together although the connection is not as explicit:

"Should I not have compassion on Nineveh, the great city in which there are more than 120,000 persons who do not know the difference between their right and left hand, as well as many animals?"

Now, oftentimes, the Old Testament will call people animals. For instance, Amos rails against some foreign wives and says, "Hear this word, you cows of Bashan who are on the mountain of Samaria, who oppress the poor, who crush the needy!" But there in Jonah the comparison between the foreigners and cattle is a little more subtle.

This idea is seen in Jonah 3:7-8 and 4:11. In 3:7-8 the author lumps man and beast together in the proclamation of the king of Nineveh who says:

"Do not let man, beast, herd, or flock taste anything. Do no let them eat or drink water. But both man and beast must be covered with sackcloth and let them call on God earnestly that each may turn from his wicked way and the violence which is in their hands." So both man and animal (what a strange idea) must be covered with sackcloth (a traditional Hebrew rite for mourning) and let them (another strange idea) call on God.

Then in 4:11 he also lumps them together although the connection is not as explicit:

"Should I not have compassion on Nineveh, the great city in which there are more than 120,000 persons who do not know the difference between their right and left hand, as well as many animals?"